Među orijentalnim sagovima nastalima tehnikom uzlanja, u fundusu Muzeja Mimara svojim oblicima posebno se ističu turkmenski sagovi. Ovi sagovi tradicionalno su se proizvodili, i još se uvijek proizvode, na području Turkestana, povijesnoga područja u Srednjoj Aziji koje obuhvaća sjeverni Afganistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, zapadni Kirgistan, južni Kazahstan i kinesku autonomnu pokrajinu Xinjiang. Naziv potječe od perzijskoga imena područja sjeverno od rijeke Amu-Darje pod vlasti turkijskih naroda (perzijski „zemlja Turkijaca“), te nikada nije označavao jedinstvenu državu, već samo područje na kojemu žive turkijski narodi. Planinski masivi Pamir i Tien Shan područje dijele na Istočni i Zapadni Turkestan. U XIII. stoljeću Turkestan se nalazio u sastavu Mongolskoga Carstva. Istočni Turkestan bio je u političkoj sferi Kine, koja ga je anektirala 1762. godine. Zapadni se Turkestan od XIV. do XVI. stoljeća nalazio u sastavu Timuridskog Carstva, a zatim pod vlašću Buharskoga, Hivskog i Kokandskog Kanata te perzijskih šahova. U drugoj polovici XIX. stoljeća zaposjeli su ga Rusi, pod čijom je vlasti ostao do raspada SSSR-a.

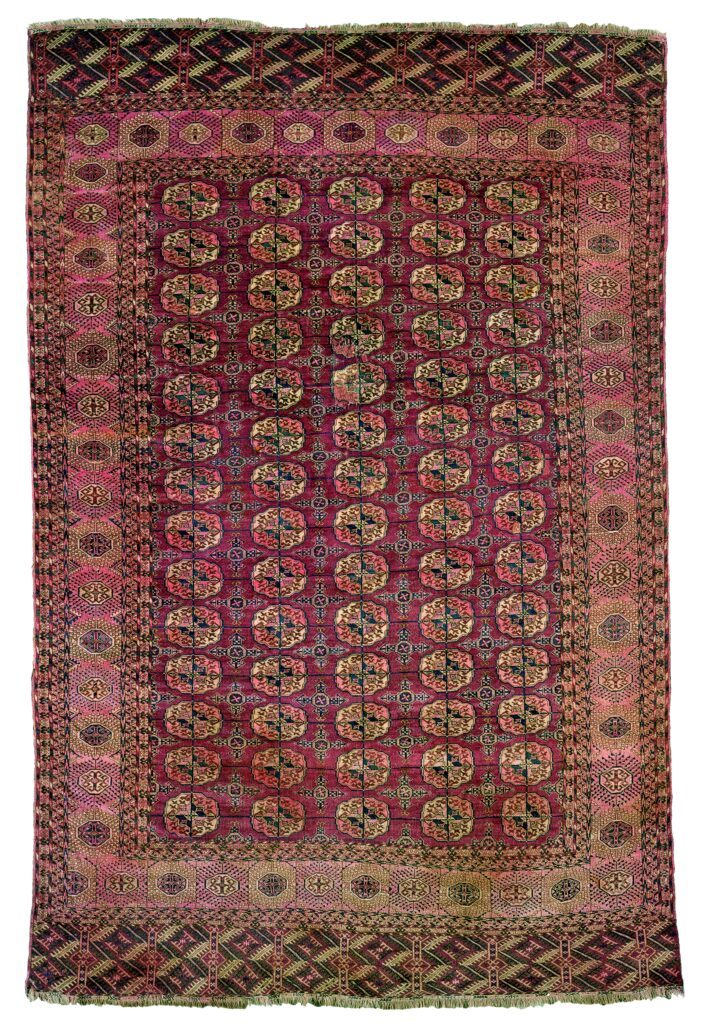

Izradom sagova tradicionalno se bave Turkmeni, turkijski narod nastanjen većinom u Turkmenistanu, ali i susjednim državama (osobito Iranu i Afganistanu) te u manjim grupama u Siriji, Iraku i Turskoj. Potomci su Oguza, skupine nomadskih turkijskih plemena koja su se iz Altajskoga gorja na područje Turkestana doselila tijekom VIII. i IX. stoljeća. U X. stoljeću prešli su na islam, kao i većina turkijskih naroda. Tradicionalno turkmensko društvo bilo je podijeljeno na poljodjelce i stočare, koji su imali veći ugled. Do početka XX. stoljeća nisu činili političku cjelinu već su bili podijeljeni na plemenske skupine (Teke, Ersari, Jomudi, Sariki, Salori, Čodori i dr.), a ta podjela zadržala se i danas. Na većinom suhome području koje su nastanjivali bavili su se nomadskim stočarstvom, a uz upotrebu navodnjavanja i poljoprivredom te sjedilačkim stočarstvom. Osim Turkmena, na području Zapadnoga Turkestana sagove izrađuju i Kazasi, Kirgizi, Uzbeci i drugi narodi. U Istočnome Turkestanu središta izrade sagova su gradovi Kashgar (Kashi), Yarkand (Shache) i Hotan, u kojima nastaju tipični sagovi s uzorkom plodova šipka, saffovi (molitveni sagovi oblikovani od nizova niša poredanih u redove) s cvjetnim motivima te sagovi s okruglim medaljonima ispunjenim rozetama (sl. 1.).

sl.1

Sag/Carpet

Hotan, Istočni Turkestan/East Turkestan

XIX. st./19th c.

pamuk (osnova), vuna; tehnika uzlanja, asimetrični čvor, 900 čvorova na dm2/cotton(warp), wool; asymmetrically knotted pile, 900 knots per dm2

179 cm x 357 cm

ATM 2482

Sagovi i drugi predmeti nastali tehnikom uzlanja bili su važan dio nomadskoga života i Turkmeni su ih jako cijenili. Osim sagova, za opremanje šatora i kućnu upotrebu izrađivali su i zastore za vrata (ensi, sl. 5.), obloge za stranice šatora, predmete za pohranu raznih veličina i namjena (chuval, torba, bokche, sl. 6. i 7.), bisage (khorjin) i prekrivala za životinje (asmalyk). Izrađivale su ih uglavnom žene na tradicionalnim tkalačkim stanovima. Sagovi za upotrebu u šatorima obično su dužine do 3 metra, dok su sagovi izrađeni za prodaju često i većih dimenzija. Od kraja XIX. stoljeća proizvodnja sagova za zapadno tržište postala je važna grana ekonomije, no iako je trgovina turkmenskim sagovima od navedenoga razdoblja značajno porasla, plemena u blizini većih gradova sagove za prodaju proizvodila su i ranije.

Među zajedničkim obilježjima turkmenskih sagova ističu se upotreba boje, prvenstveno crvene u rasponu od smećkasto-crvenih do gotovo ljubičastih tonova, uz plavu, zelenu, bijelu i žutu, te upotreba karakterističnih motiva zvanih göl (gul, gol). Gölovi su motivi obično osmerokutnoga oblika koji se ponavljaju kao glavni motivi na poljima turkmenskih sagova, te kao ispuna područja između glavnih motiva. Njihovo porijeklo nije do kraja razjašnjeno. Na temelju sličnosti s perzijskom riječi gul (cvijet) i turskom riječi gül (ruža) nastala je teza kako se radi o stiliziranome cvjetnom motivu, rozeti. Ruska etnologinja Valentina Georgievna Moškova predložila je tezu kako gölovi predstavljaju ambleme turkmenskih plemena. Pojedina plemena povezana su s određenim gölom koji, kada se koristi kao glavni motiv, omogućuje osnovnu atribuciju saga. No, ovisno o promjenjivoj sudbini plemena koja su se tijekom povijesti asimilirala ili izumirala, mijenjali su se i gölovi koje su koristili zbog čega atribucija samo na temelju gölova nije dostatna te joj se priključuje i strukturna analiza sagova (materijal, vrsta čvora, gustoća čvorova i sl.). Osnovni materijal za izradu je vuna, u novije vrijeme i pamuk, a svila se ponekad koristi za naglašavanje važnih motiva. U turkmenskim sagovima obično se koriste asimetrični čvorovi, iako poneka plemena koriste i simetrične čvorove.

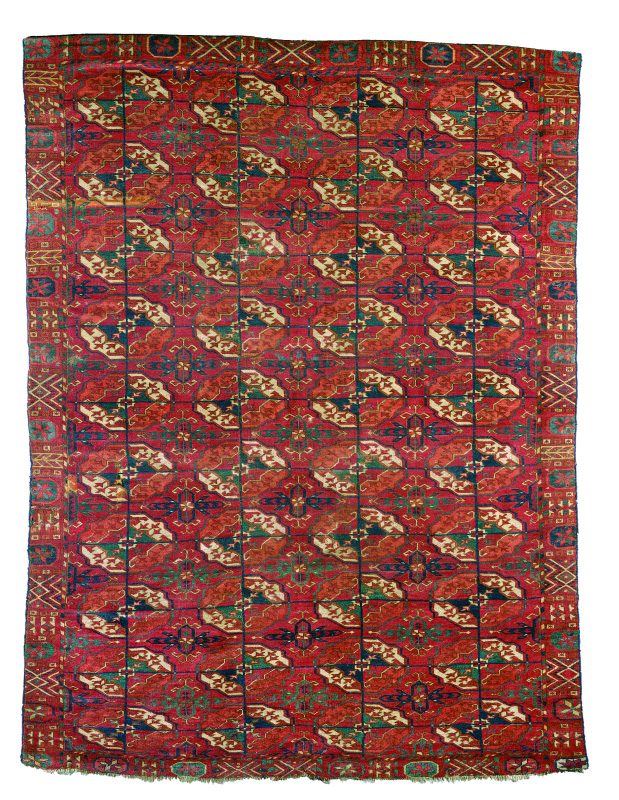

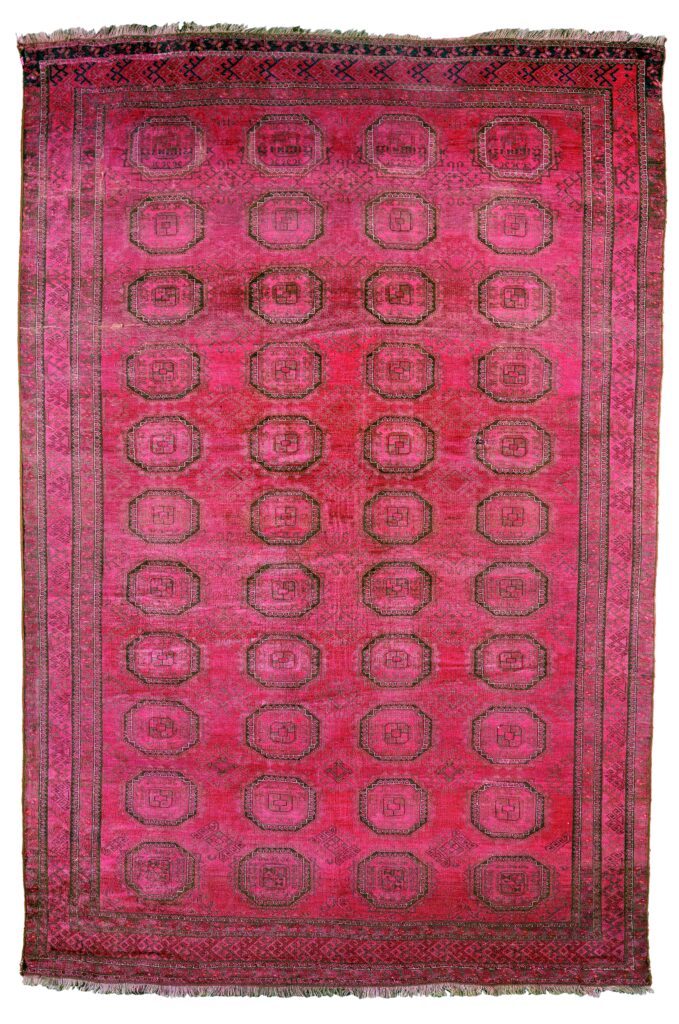

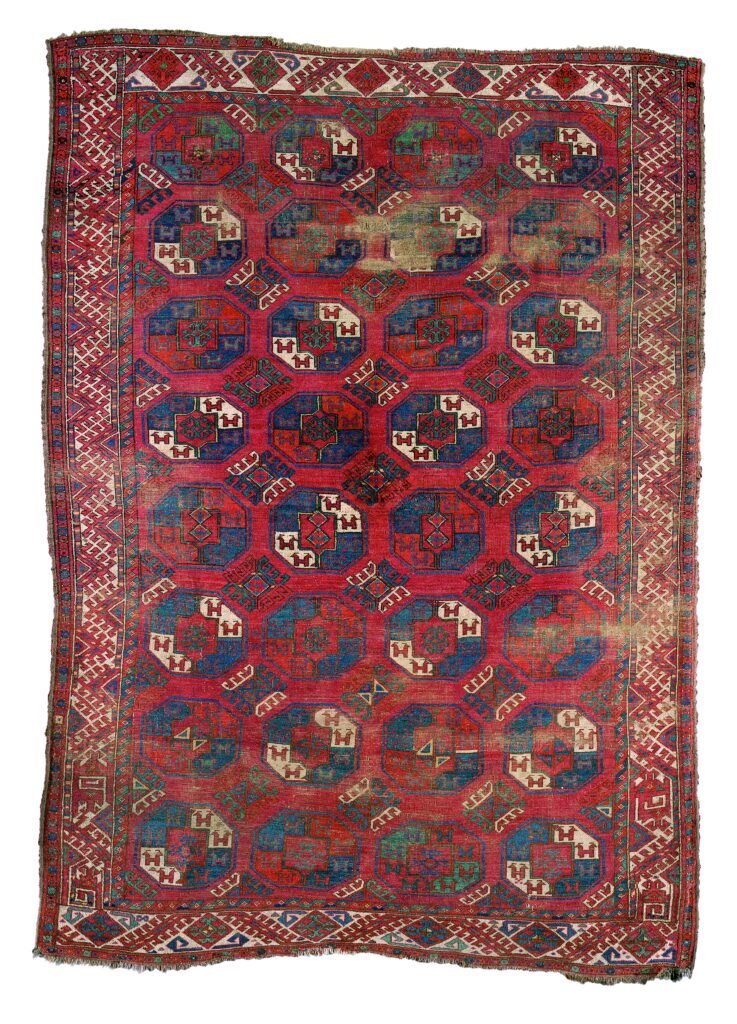

U sagovima plemena Teke koristi se asimetrični čvor, a često imaju dvije niti potke. Osnovni göl Tekea je stepeničast osmerokut ukrašen stiliziranim grančicama s lišćem. Unutrašnjost göla je četvorena plavim linijama koje se nastavljaju izvan göla te tvore pravilan raster. Četvrtine göla obojane su naizmjenično crveno i krem u vanjskome dijelu te crveno i crno, plavo ili zeleno u unutarnjem dijelu (sl. 2., 3., 4.). Sporedni göl obično je križnoga oblika s kukastim završetcima (sl. 2. i 3.). Na sagu ATM 2496 nalazimo chemche göl, koji se javlja kao sporedni göl na turkmenskim sagovima neovisno o plemenu (sl. 4.). Uži dijelovi saga često su produženi poljima sa stiliziranim biljnim ili geometrijskim motivima (sl. 3.), a obično se na njima nalaze i široke crvene tkane trake, koje međutim često nedostaju (sl. 2.).

sl.2

Sag, Teke/Tekke Carpet

Srednja Azija/Central Asia

sredina XIX. st./mid-19th c.

vuna; tehnika uzlanja, asimetrični čvor, 2400 čvorova na dm2/wool; asymmetrically knotted pile, 2400 knots per dm2

191 cm x 220 cm

ATM 2498

Sag, Teke/Tekke Carpet

Srednja Azija/Central Asia

druga pol. XIX. st./second half of 19th c.

vuna; tehnika uzlanja, asimetrični čvor, 2000 čvorova na dm2/wool; asymmetrically knotted pile, 2000 knots per dm2

224 cm x 338 cm

ATM 1707

Sag, Teke/Tekke Carpet

Srednja Azija/Central Asia

sredina XIX. st./mid-19th c.

vuna; tehnika uzlanja, asimetrični čvor, 2000 čvorova na dm2/wool; asymmetrically knotted pile, 2000 knots per dm2

155 cm x 210 cm

ATM 2496

Ensi, Teke/Tekke Ensi

Srednja Azija/Central Asia

XIX. st./19th c.

vuna; tehnika uzlanja, asimetrični čvor, 2400 čvorova na dm2/wool; asymmetrically knotted pile, 2400 knots per dm2

125 cm x 140 cm

ATM 2466

Pleme Sarik u svojim sagovima koristi simetrične i asimetrične čvorove te po dvije niti potke. Sagovi s kraja XIX. stoljeća imaju ljubičasto-smeđa polja, dok su na ranijima polja obično grimizno crvena. Osnovni göl Sarika je stepeničasti osmerokut s upisanim šesterokutom, a na sagu ATM 2497 takav se oblik ponavlja i u sporednome gölu, no s različitim središnjim ukrasom (sl. 6.). U središtima glavnoga göla javlja se motiv kochak (ovnov rog), koji se ponavlja i na borduri. Česta je upotreba vrlo tamnih tonova plave i zelene.

sl.6

Chuval, Sarik/Saryk Chuval

Srednja Azija/Central Asia

XIX. st./19th c.

vuna; tehnika uzlanja, asimetrični čvor, 2000 čvorova na dm2/wool; asymmetrically knotted pile, 2000 knots per dm2

136 cm x 100 cm

ATM 2497

Osmerokutni göl s nizom trokutastih istaka s kukastim zaključcima duž vanjske i unutarnje strane povezan je sa Salorima, no od sredine XIX. stoljeća koriste ga i Teke, Sarici, Ersari i Kizil-Ajaci. Središte göla često je ružičaste boje (sl. 7. i 8.). Sporedni göl križnoga oblika oblikovan je od kvadratića s motivom aina-kochak u središtu (sl. 7.). Dok se motivi Salora mogu pronaći i kod drugih plemena, za njihove predmete karakterističan je velik broj čvorova.

sl.7

Chuval, Salor/Salor Chuval

Srednja Azija/Central Asia

sredina XIX. st./mid-19th c.

vuna; tehnika uzlanja, asimetrični čvor, 3500 čvorova na dm2/wool; asymmetrically knotted pile, 3500 knots per dm2

122 cm x 78 cm

ATM 2500

sl.8

Sag, Kizil-Ajak/Kizil Ayak Carpet

Srednja Azija/Central Asia

kraj XIX. st./end of 19th c.

vuna; tehnika uzlanja, asimetrični čvor, 900 čvorova na dm2/wool; asymmetrically knotted pile, 900 knots per dm2

243 cm x 356 cm

ATM 2499

Kizil-Ajaci smatraju se podgrupom plemena Ersari, i koriste asimetrične čvorove. Osnovni göl koji koriste je tauk-noska, četvoreni osmerokutni göl s parom dvoglavih životinja u svakoj četvrtini (sl. 9.), koji koriste i Ersari, Arabači, Jomudi i Čodori. Sporedni göl na sagovima ATM 2499 i ATM 2563 oblikovan poput romba s nizom kukastih istaka na stranicama (sl. 8. i 9.) naziva se dyrnak göl i koriste ga Jomudi, Čodori, Čubaši i Ersari.

sl.9

Sag, Kizil-Ajak/Kizil Ayak Carpet

Srednja Azija/Central Asia

sredina XIX. st./mid-19th c.

vuna; tehnika uzlanja, asimetrični čvor, 900 čvorova na dm2/wool; asymmetrically knotted pile, 900 knots per dm2

200 cm x 280 cm

ATM 2563

Gölovi su zasigurno najupečatljivije obilježje turkmenskih sagova. Njihovom usporedbom i komparativnom strukturnom analizom sagova dolazimo do atribucije, koja nikako nije konačna, već kao i brojna pitanja o nastanku i razvoju gölova te plemenima koja ih koriste, čeka daljnje odgovore.

Turkmen Carpets in the Mimara Museum

Among the oriental knotted pile rugs in the holdings of the Mimara Museum, the designs of Turkmen rugs stand out the most. These rugs have traditionally been produced, and are still produced, in the Turkestan area, a historic area in Central Asia that includes northern Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, western Kyrgyzstan, southern Kazakhstan, and the autonomous Chinese province of Xinjiang. The name derives from the Persian word for the area north of the river Amu Darya under the rule of the Turkic peoples (Persian “land of the Turkic”), and it never denoted a single state, but only the area inhabited by the Turkic peoples. The Pamir and Tian Shan mountain ranges divide the area into East and West Turkestan. In the 13th century, Turkestan was part of the Mongol Empire. East Turkestan was in the political sphere of China, which annexed it in 1762. Since the 14th until the 16th century West Turkestan was part of the Timurid Empire, and then under the rule of Khanates of Bukhara, Khiva and Kokand and the Persian shahs. In the second half of the 19th century, it was occupied by the Russians, under whose rule it remained until the collapse of the USSR.

The carpets are traditionally made by Turkmen, Turkic people living mostly in Turkmenistan, but also in neighboring countries (especially Iran and Afghanistan) as well as in smaller groups in Syria, Iraq and Turkey. They are descendants of the Oghuz, a group of nomadic Turkic tribes who immigrated to the Turkestan area from the Altai Mountains during the 8th and 9th century. In the 10th century, they converted to Islam, as did most Turkic peoples. Traditional Turkmen society was divided into farmers and herders, who held more prestige. Until the beginning of the 20th century, they were not politically united but were divided into tribal groups (Tekke, Ersari, Yomut, Saryk, Salor, Chodor, etc.), and this division has persisted until today. In the mostly dry area they inhabited, they were engaged in nomadic cattle breeding, and with the use of irrigation, they also engaged in agriculture and sedentary cattle breeding. Apart from Turkmen, carpets are also made in the area of West Turkestan by Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Uzbeks and other peoples. In East Turkestan, the centers of rug making are the cities of Kashgar (Kashi), Yarkand (Shache) and Hotan, where typical pomegranate-fruit patterned rugs, saffs (prayer rugs designed with a series of niches arranged in rows) with floral motifs, and rugs with round medallions with rosettes are created (Fig. 1).

Carpets and other objects with a knotted pile were an important part of nomadic life and were highly valued by the Turkmen. In addition to carpets, to furnish tents and for daily use, they also made door curtains (ensi, Fig. 5), linings for the sidewalls of their tents, storage items of various sizes and purposes (chuval, torba, bokche, Figs. 6 and 7), saddle bags (khorjin) and animal covers (asmalyk). They were made mainly by women on traditional looms. Carpets for use in tents are usually up to 3 meters long, while rugs made for sale are often of larger dimensions. From the end of the 19th century, carpet production for the western market has become an important branch of the economy, but although the trade in Turkmen carpets has increased significantly since that period, tribes near major cities have produced carpets for sale before.

Among the common features of Turkmen rugs are the use of color, primarily red in the range from brownish-red to almost purple tones, with blue, green, white and yellow, and the use of characteristic motifs called göl (gul, göl). Göls are usually octagonal in shape, repeated as the main motifs in Turkmen rugs, and as a filling of the area between the main motifs. Their origin is not fully clear. Based on the similarity with the Persian word gul (flower) and the Turkish word gül (rose), there is a theory that göls are stylized floral motifs, rosettes. Russian ethnologist Valentina Georgievna Moshkova proposed the theory that göls represent the emblems of Turkmen tribes. Individual tribes are associated with a particular göl which, when used as the main motif, allows for the basic attribution of the carpet. However, depending on the changing fate of the tribes that have become assimilated or extinct throughout history, the göls they used have changed, which is why attribution based on göls alone is not sufficient, and structural analysis (material, type of knots, knot density, etc.) is needed as well. The basic material for carpet making is wool, more recently cotton, while silk is sometimes used to emphasize important motifs. Asymmetrical knots are usually used in Turkmen rugs, although some tribes use symmetrical knots as well.

Asymmetrical knots are used in Tekke rugs, and they often have two weft threads. The basic Tekke göl is a stepped octagon decorated with stylized twigs with leaves. The inside of the göl is quartered with blue lines that continue outside the göl thus forming a regular grid. The quarters of the göl are colored alternately red and cream on the outside and red and black, blue or green on the inside (Figs. 2, 3, 4). The secondary göl is usually cross-shaped with hooked ends (Figs. 2 and 3). On the ATM 2496 rug we find the chemche göl, which occurs as a secondary göl on Turkmen rugs regardless of tribe (Fig. 4). The narrower parts of the rug are often extended by fields with stylized plant or geometrical motifs (Fig. 3), and there are usually wide red woven bands on them, which, however, are often missing (Fig. 2).

The Saryk tribe uses symmetrical and asymmetrical knots and two weft threads in their rugs. Carpets from the end of the 19th century have purple-brown fields, while on those from earlier times the fields are usually scarlet red. The basic Saryk göl is a stepped octagon with an inscribed hexagon. On the ATM 2497 carpet, such a shape is repeated as the secondary göl, but with a different central decoration (Fig. 6). The kochak (ram’s horn) motif appears in the centers of the main göl, as well as on the border. The use of very dark tones of blue and green is common. An octagonal göl with a series of triangular protrusions with hooked ends along the outside and inside is associated with Salors, but from the middle of the 19th century it was also usedby the Tekke, Saryk, Ersari and Kizil Ayaks. The center of the göl is often pink (Figs. 7 and 8). The cross-shaped secondary göl is formed from squares with the aina-kochak motif in the center (Fig. 7). While Salor motifs can also be found in other tribes, their weavings are characterized by a large number of knots.

The Kizil Ayaks are considered a subgroup of the Ersari tribe, and they use asymmetrical knots. The basic göl they use is tauk-noska, a square octagonal göl with a pair of two-headed animals in each quarter (Fig. 9), which is also used by the Ersari, Arabachi, Yomut and Chodor tribes. The secondary göl on the ATM 2499 and ATM 2563 rugs, shaped like a diamond with a series of hook-like protrusions on the sides (Figs. 8 and 9), is called a dyrnak göl and is used by the Yomudi, Chodor, Chubash and Ersari tribes.

Göls are certainly the most striking feature of Turkmen rugs. Their comparison and comparative structural analysis of carpets lead to an attribution of the rugs, which is by no means final, but like numerous questions about the origin and development of göls and the tribes that use them, awaits further answers.

Literatura/Literature:

Ribičić-Županić, Anica. Orijentalni sagovi u Muzeju Mimara. Zagreb: Muzej Mimara, 2009.

Pinner, Robert; Eiland, Murray Lee Jr. Between the Black Desert and the Red. Turkmen Carpets from the Wiedersperg Collection. San Francisco: Fine Arts Museum, 1999.

Mackie, Louise; Thompson, Jon. Turkmen. Tribal Carpets and Traditions. Washington: The Textile Museum, 1980.

Bennett, Ian. Weaving of the Turkoman and Baluchi Tribes // The Country Life Book of Rugs and Carpets of the World (ur. Ian Bennett). London: Quarto Publishing Ltd., 1978.