Prednja strana slike ona je s kojom ćemo se najprije susresti te ona na koju se najčešće oslanjamo kako bismo dobili informacije o umjetničkome djelu. Analize koje povjesničari umjetnosti provode tijekom povijesno-umjetničkoga istraživanja – formalna, komparativna, ikonografska – temelje se na promatranju umjetničkoga djela, pri čemu je susret sa stvarnim djelom, a ne reprodukcijom, ključan preduvjet uspješnoga istraživanja. Zajedno s arhivskim istraživanjima i upoznavanjem s trenutno dostupnom stručnom literaturom o temi koja se istražuje, one omogućuju davanje prijedloga atribucije i datacije te vrednovanje djela u kontekstu opusa autora ili tadašnje umjetničke produkcije, kao i kasnije uloge djela u baštini.

Sakupljena u muzejima kao muzejski predmeti, umjetnička djela svjedoče o okolnostima (vremenu, prostoru, kulturi, običajima, tehničkim dostignućima) u kojima su nastala, odnosno, u novoj, muzealnoj stvarnosti ona su dokumenti stvarnosti iz koje su izdvojena. Međutim, ta stvarnost nije ograničena samo na trenutak njihova nastanka pa tako umjetnička djela, osim o svojim autorima i naručiteljima, svjedoče i o svojim kasnijim vlasnicima, promjenama ukusa tijekom vremena, načinima i uzorcima sakupljanja i trgovanja umjetninama, ukratko svjedoče o povijesnom, društvenom i ekonomskom kontekstu vremena u kojem postoje. Upravo u tome protoku vremena i promjenama okolnosti nalazi se područje istraživanja provenijencije, a tragovi tih promjena često su zabilježeni na samim predmetima.

.

PROVENIJENCIJA

Pod pojmom provenijencije (od franc. glagola provenir „potjecati“) povjesničari umjetnosti i muzejski stručnjaci podrazumijevaju povijest promjena vlasništva i smještaja umjetničkoga djela od trenutka njegova nastanka do sadašnjega vremena. U idealnim uvjetima istraživanje provenijencije može pomoći u atribuciji nekoga djela, no u većini slučajeva s njome neće biti neposredno povezano. Potpuna provenijencija podrazumijeva točan popis vlasnika djela, odnosno njegova smještaja, od sadašnjega vremena do trenutka i mjesta njegova nastanka. Istraživanje provenijencije zahtjevan je posao koji uvelike ovisi o količini i dostupnosti relevantnih izvora, pa su potpune provenijencije rijetkost, a praznine u provenijenciji česta pojava, osobito za starija djela.

Izvori za istraživanje provenijencije vrlo su raznoliki te obuhvaćaju aukcijske kataloge, kataloge zbirki i izložaba, znanstvene studije i monografije, arhivske izvore poput novinskih članaka, arhiva prodavača, korespondencije prodavača i kupaca, različitih inventarnih popisa, te muzejsku dokumentaciju. Primarni izvor informacija o provenijenciji umjetničkoga djela često se nalazi na poleđini samoga djela u obliku raznih oznaka. U tom kontekstu, prednja strana djela i njegova poleđina jednako su vrijedan izvor znanja o djelu pa povjesničari umjetnosti i muzejski stručnjaci svoju pažnju često posvećuju i toj obično skrivenoj strani umjetničkih djela.

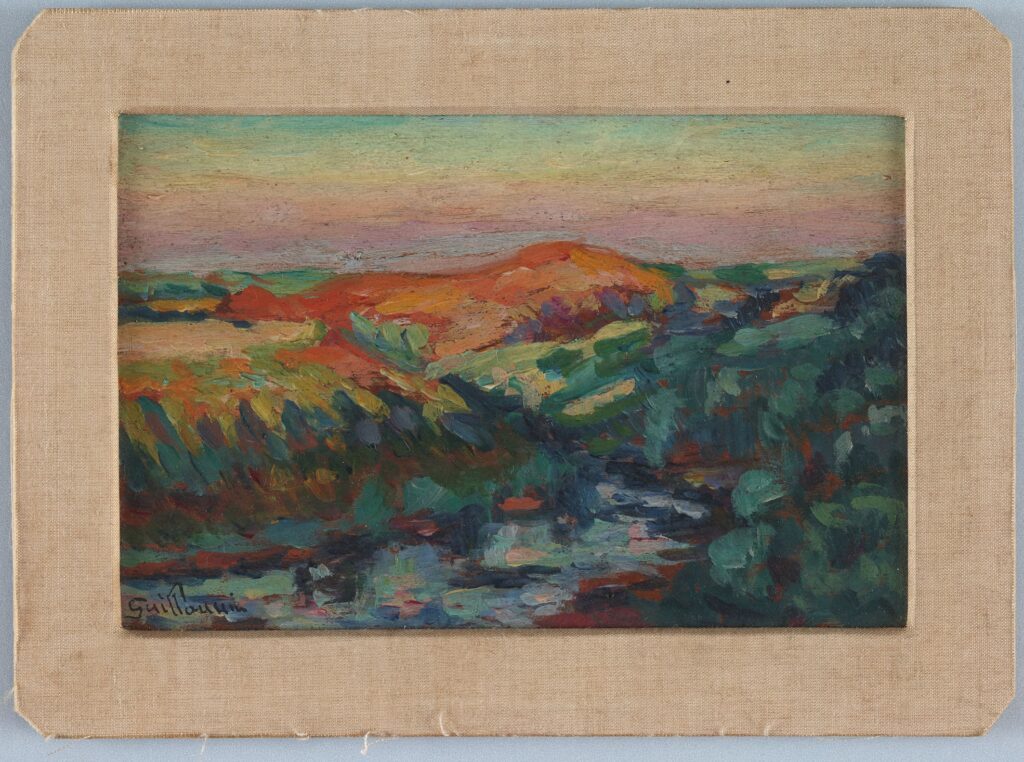

Armand Guillaumin

Krajolik / Landscape

Francuska, poč. XX. st. / France, beginning of 20th c.

ulje na drvu / oil on panel

8,5 cm x 13,5 cm

ATM 764

sl. 1

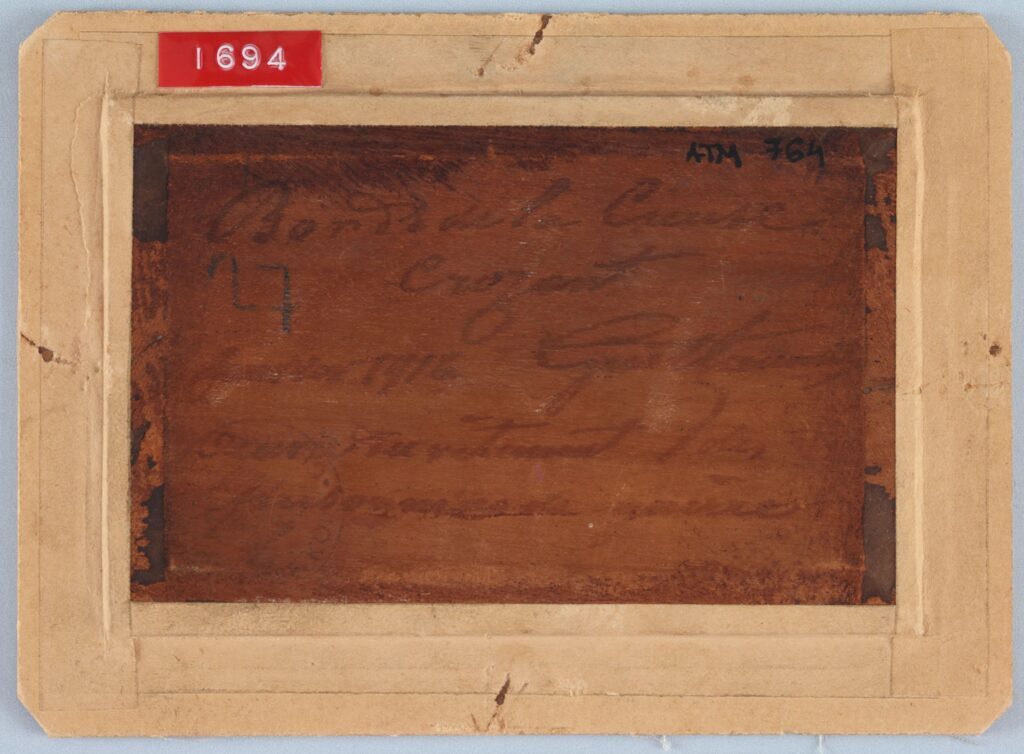

Poleđina sl. 1 / The reverse of fig. 1

sl. 2

Armand Guillaumin

Krajolik uz more / Landscape by the Sea

Francuska, poč. XX. st. / France, beginning of 20th c.

ulje na drvu / oil on panel

8,5 cm x 12,8 cm

ATM 765

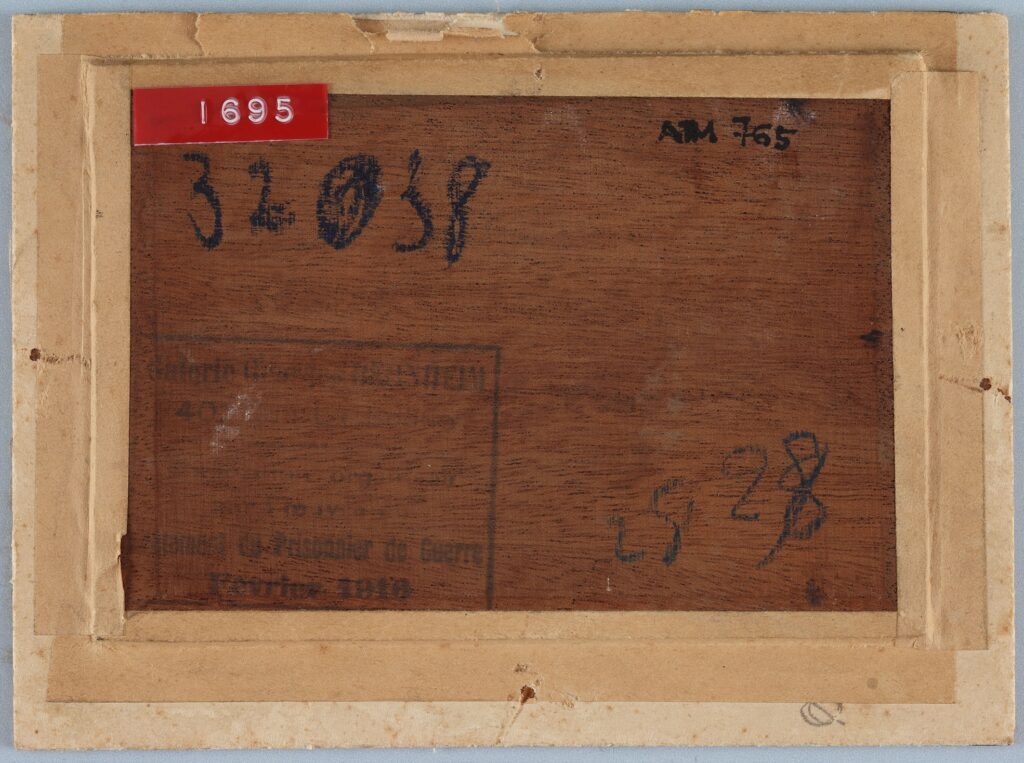

sl. 3

Poleđina sl. 3 / The reverse of fig. 3

sl. 4

OZNAKE NA POLEĐINI DJELA

Oznake na poleđini slika mogu biti vrlo raznolike te pružati niz informacija o autoru djela, smještaju i promjenama smještaja djela, vlasnicima i prijenosu vlasništva djela poput aukcija, darovanja i slično, te izložbama na kojima je djelo izlagano. Također, materijal nositelja slikanoga sloja, način na koji je s njime postupano te njegovo stanje, a što je vidljivo tek s poleđine slike, mogu pružiti vrijedne informacije o podrijetlu djela, naknadnim intervencijama ili uvjetima u kojima je djelo čuvano.

Iako se potpisi autora najčešće nalaze na prednjoj strani slike, ponekad se mogu pronaći i na njezinoj poleđini. Autentičan potpis pružit će (ili potvrditi) atribuciju djela, a ako se autorov potpis mijenjao tijekom vremena, može omogućiti i precizniju dataciju djela. Uz svoj potpis autori djelo ponekad imenuju, datiraju, označe mjesto nastanka ili napišu posvetu koja nam pruža više informacija o tome za koga je djelo nastalo ili koja mu je namjena.

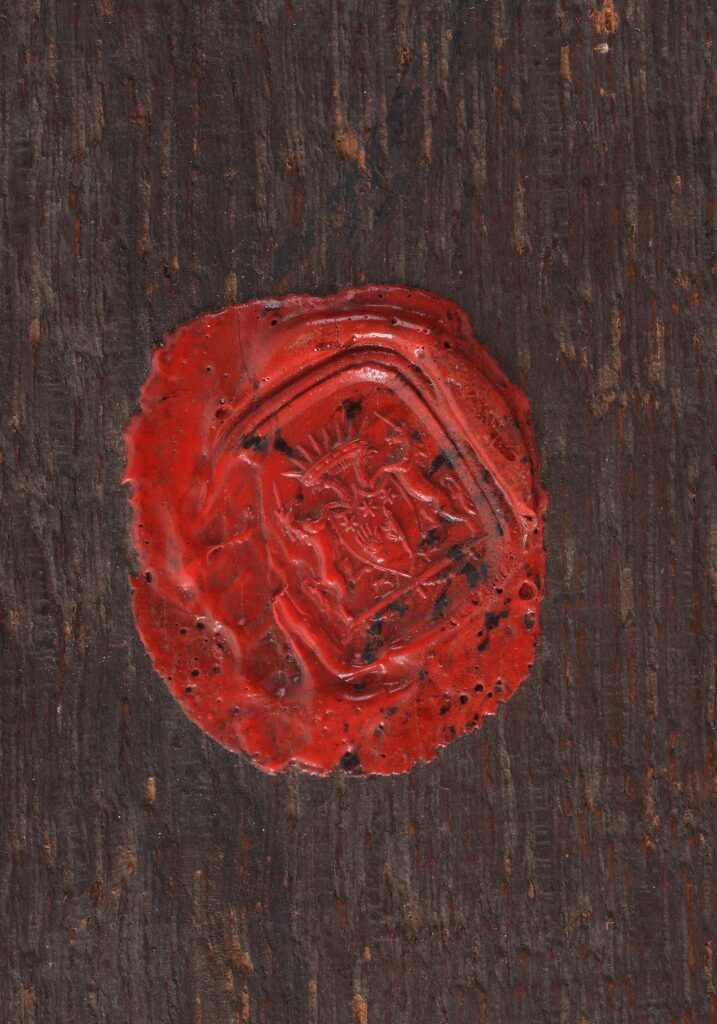

Vlasnici slika na njima mogu ostaviti tragove svoga vlasništva u obliku natpisa ili oznaka, a koje uključuju potpise, inicijale, monograme, pečate i grbove. Obiteljski grbovi često su na pozadine slika otisnuti voštanim pečatima. Na poleđini slike Krajolik s putnikom nepoznatoga autora (sl. 5.) u crvenom je vosku utisnut kvadratičan grbovni pečat s cjelovito sačuvanim grbom (sl. 6.).

nepoznat autor / unknown author

Krajolik s putnikom / Landscape with a Traveler

Nizozemska, XVII. st. / Holland, 18th c.

ulje na drvu / oil on panel

24,8 cm x 35,4 cm

ATM 2011

sl. 5

sl. 6

Grbni štit u dnu je šiljasto zaključen, dok je na vrhu zaključen trima šiljcima. Uz vrh grbnoga polja nalaze se tri šesterokrake zvijezde ispod kojih se nalaze ruka na čijem je dlanu oko te figura propeta na jednu nogu. Štit sa svake strane pridržavaju dva jednoroga, dok ga sa stražnje strane pridržava okrunjeni dvoglavi orao. Pripadnost grba još nije sa sigurnošću utvrđena, no grb pokazuje sličnosti (motiv ruke s okom, tri zvijezde, jednorozi) s grbom fanariotske obitelji Manos. [1]

Promjene lokacije slika mogu se pratiti i u slučaju da se na njima nalaze carinski pečati ili oznake drugih državnih tijela. Carinski pečati ukazuju na to da se slika u određenom trenutku nalazila na prostoru države čija je carinska služba ostavila pečat. Na poleđini portreta Eleonore Portugalske (sl. 7.) nalaze se dva takva pečata. U gornjem desnom dijelu poleđine slike smješten je okrugao pečat otisnut tintom (sl. 8).

Portret Eleonore Portugalske / Portrait of Eleanor of Portugal

Flandrija, poč. XVI. st. / Flanders, beginning of 16th c.

ulje na drvu / oil on panel

49 cm x 40 cm

ATM 795

sl.7

Detalj poleđine sl. 7 / Detail of the reverse of fig. 7

sl. 8

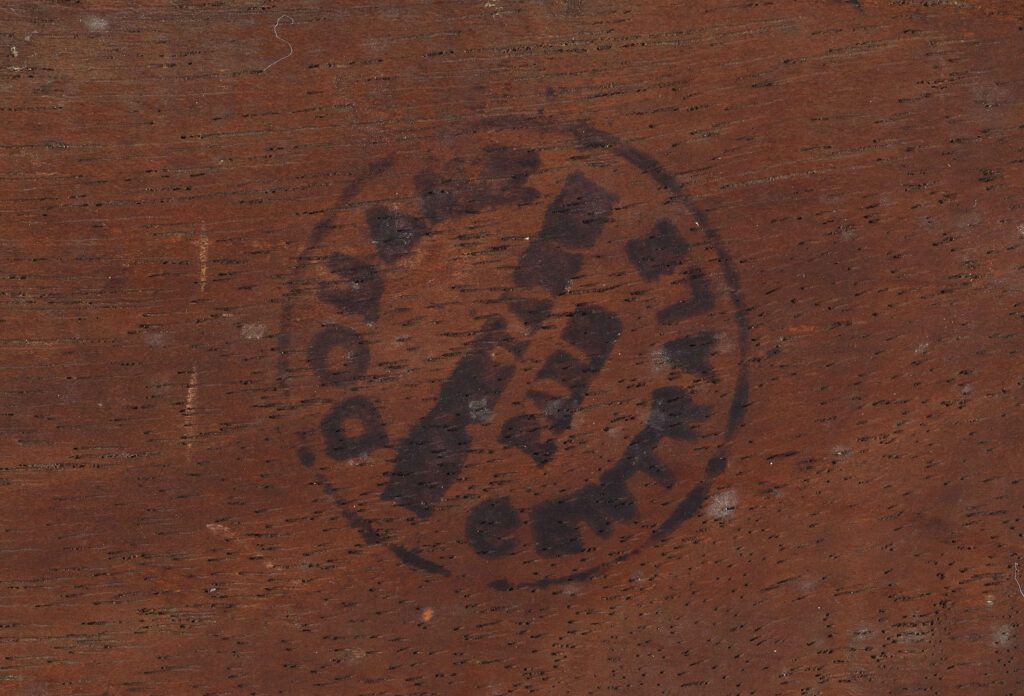

Iako je natpis u pečatu zamrljan, uz rub pečata može se iščitati DOUANE CENTRALE, a u središnjem teško čitljivom natpisu, tek se u donjoj riječi razabire PAR[…]. Iz prisutnosti ovoga pečata možemo zaključiti da je slika u nekom trenutku prošla carinsku kontrolu, i to pretpostavljamo na području Francuske. Na istoj slici lijevo od središnje osi prema dnu nalazi se još jedan okrugao pečat otisnut tintom (sl. 9.).

Detalj poleđine sl. 7 / Detail of the reverse of fig. 7

sl. 9

Rub pečata tvore dvije linije, a u sredini jedna linija okružuje središnji grb. Između linija nalazi se natpis BUNDESDENKMALAMT te kraći nečitljiv natpis odvojen zvjezdicama. Bundesdenkmalamt austrijsko je federalno tijelo nadležno za poslove očuvanja, zaštite, obnove i istraživanja kulturne baštine. Osnovano je 1850. godine odlukom cara Franje Josipa I. kao K.k. Central-Commission zur Erforschung und Erhaltung der Baudenkmale. [2] Pečat Bundesdenkmalamta na poleđini umjetničkoga djela ukazuje na to da je predmetu u prošlosti dopušten izvoz iz Austrije.

Ako se slika ikada našla na prodaji u aukcijskoj kući ili galeriji, dodijeljen joj je inventarni broj. Aukcijske kuće za tu su namjenu uobičajeno koristile kredu – u slučaju kuće Sotheby’s riječ je o žutoj kredi – ili tintu. Christie’s je početkom XIX. stoljeća koristio crnu tintu, no oznake je tijekom vremena mijenjao, a danas se slike obično označuju naljepnicama s barkodom. Usporedbom inventarnoga broja s podacima u arhivi aukcijske kuće ili galerije moguće je utvrditi gdje i kada je djelo prodano, a ponekad i tko ga je prodao i po kojoj cijeni. Ovi podaci od iznimne su važnosti u utvrđivanju provenijencije djela, ali i promjena atribucija djela u prošlosti. Promjene atribucije i/ili imena djela u prošlosti otežavaju neupitno utvrđivanje identiteta djela koje istražujemo kao onoga koje se spominje u korespondenciji i inventarnim popisima kolekcionara ili u literaturi.

Slikama, ali i drugim predmetima, inventarni brojevi također se dodjeljuju kada postanu dio muzejske zbirke, a ponekad se posebne oznake dodjeljuju predmetima posuđenima za izlaganje izvan muzeja. Svim predmetima u fundusu Muzeja Mimara dodijeljeni su inventarni brojevi koji sadrže slovni dio koji označava kôd muzeja utvrđen u stručnom registru Muzejskog dokumentacijskog centra u Zagrebu te brojčani dio koji označava redoslijed ulaska predmeta u inventar fundusa muzeja. Inventarne oznake u pravilu se nanose izravno na predmet, osim u slučaju kada bi se nanošenjem oznake predmet mogao oštetiti. U tom slučaju oznake se zabilježuju na drugom mediju te pridružuju predmetu.

Joos van Cleve

Isus i sv. Ivan Krstitelj kao dječaci / Jesus and St. John the Baptist as children

Flandrija, 1530.-ih / Flanders, 1530s

ulje na drvu / oil on panel

13,2 cm x 19,5 cm

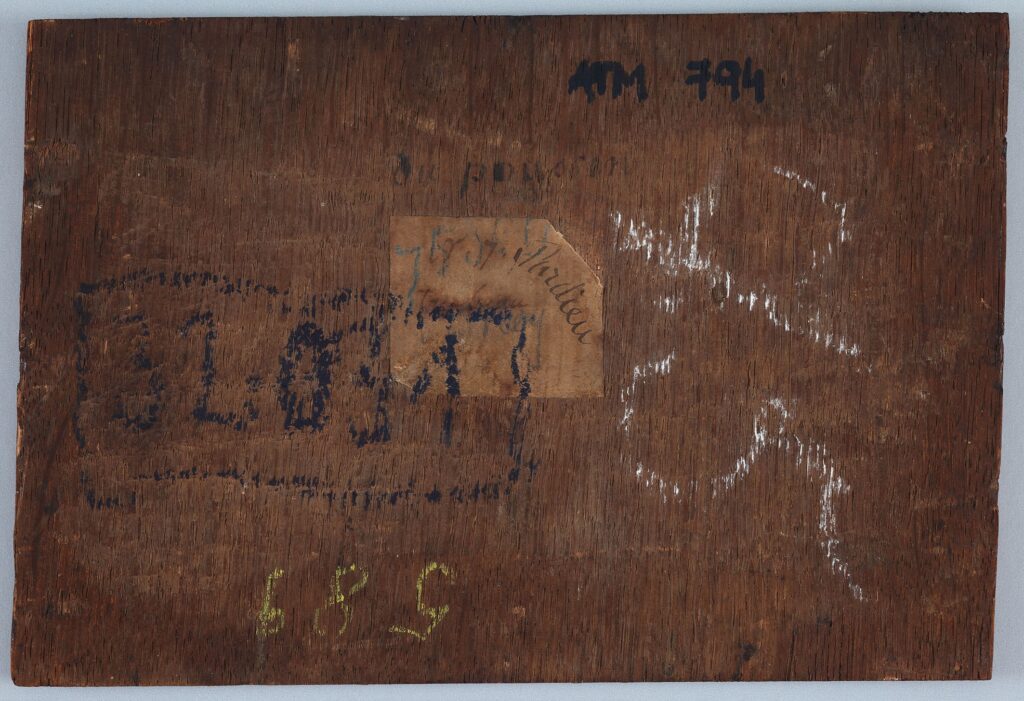

ATM 794

sl. 10

Poleđina sl. 10 / The reverse of fig. 10

sl. 11

Carl Spitzweg

Portretiranje / Portraiture

Njemačka, 1875. / Germany, 1875

ulje na drvu / oil on panel

11,2 cm x 15 cm

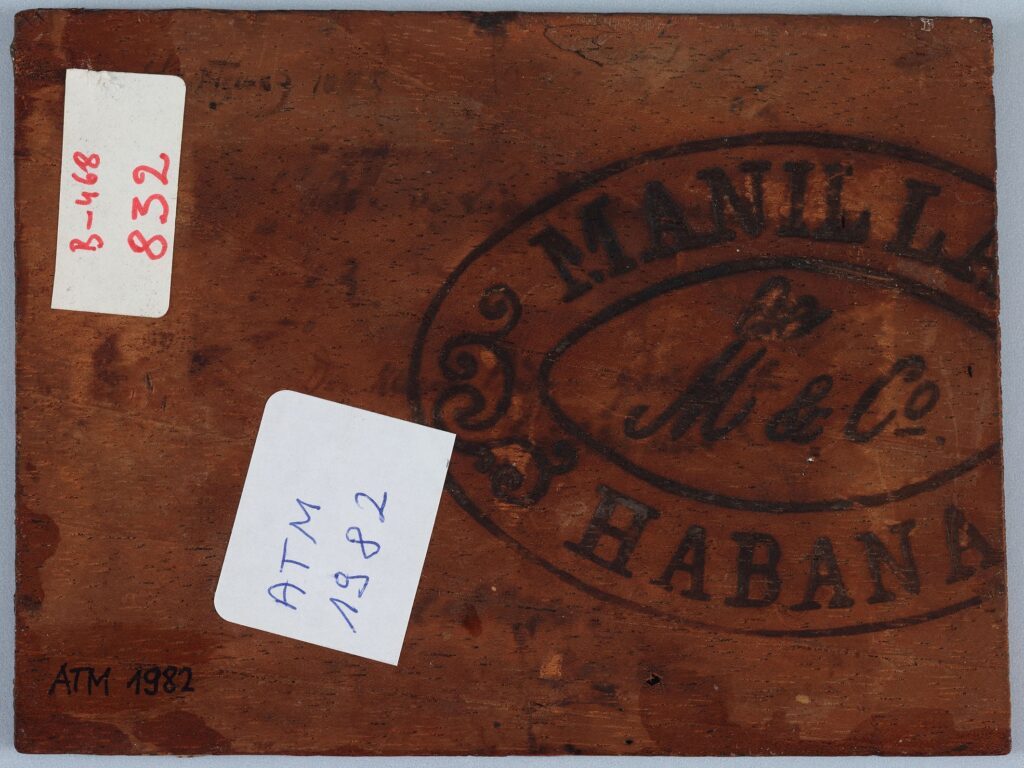

ATM 1982

sl. 12

Poleđina sl. 12 / The reverse of fig. 12

sl. 13

Na pozadini slike, dodatne informacije ne dolaze samo od natpisa i oznaka, već i od materijala korištenoga u izradi slike. Izbor materijala može upućivati na vrijeme, ali i regiju u kojoj je slika nastala. Od XV. stoljeća, drvene daske zamjenjuju se platnom kao nositeljem, što je omogućilo veće formate slika. Na nositeljima se ponekad nalaze oznake proizvođača koje mogu pomoći u pobližem određivanju mjesta i/ili vremena nastanka slike. Izbor materijala i način izrade nositelja, odnosno vrsta spoja dasaka u slučaju slike na dasci, ili vrsta spoja podokvira platna u slučaju slike na platnu, razlikuju se ovisno o mjestu i vremenu nastanka. Promjene na materijalu mogu nam dati informacije i o uvjetima u kojima se slika čuvala ili je bila izložena. Ispucani slikani sloj ili pukotine u drvu, mogu upućivati na vruće i suhe uvjete, a iskrivljeni nositelji pak na to da se slika nalazila u vlažnim uvjetima.

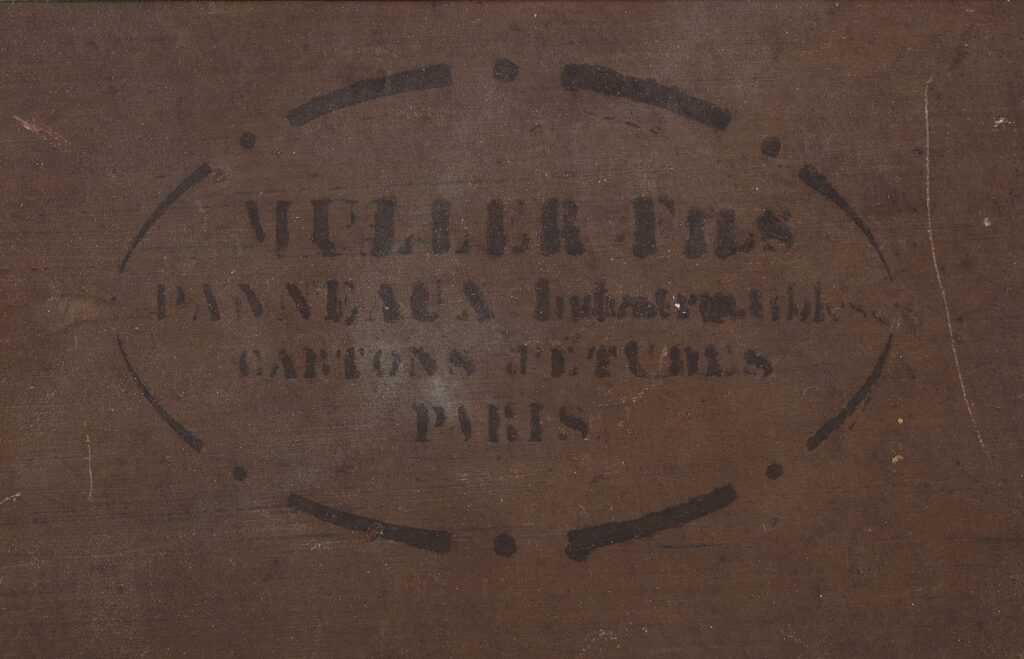

Na poleđini Portreta žene (sl. 14.) nalazi se ovalni pečat s natpisom: MULLER FILS / PANNEAUX INDESTRUCTIBLES / CARTONS d’ÉTUDES / PARIS (sl. 15.).

Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot

Portret žene / Portrait of a Woman

Pariz, 1830.-ih / Paris, 1830s

ulje na ploči / oil on panel

32,2 cm x 24 cm

ATM 771

sl. 14

Detalj poleđine sl. 14 / Detail of the reverse of fig. 14

sl. 15

Tvrtka Muller Fils djelovala je u Parizu od 1842. do 1855. godine pod vodstvom Edmonda Frédérica Mullera, a bavila se proizvodnjom i prodajom slikarskih potrepština (boja, slikarskih platna, ploča, lakova). [3] Tijekom navedenoga razdoblja zabilježena je i pod nazivima Muller Fils & Compagnie te Muller Fils & Cie. Za proizvodnju bezbojnoga slikarskog laka te neuništivih ploča, tvrtki su izdani patenti 1840. i 1844. godine, [4] a iste je godine izlagala na Francuskoj industrijskoj izložbi u Parizu.

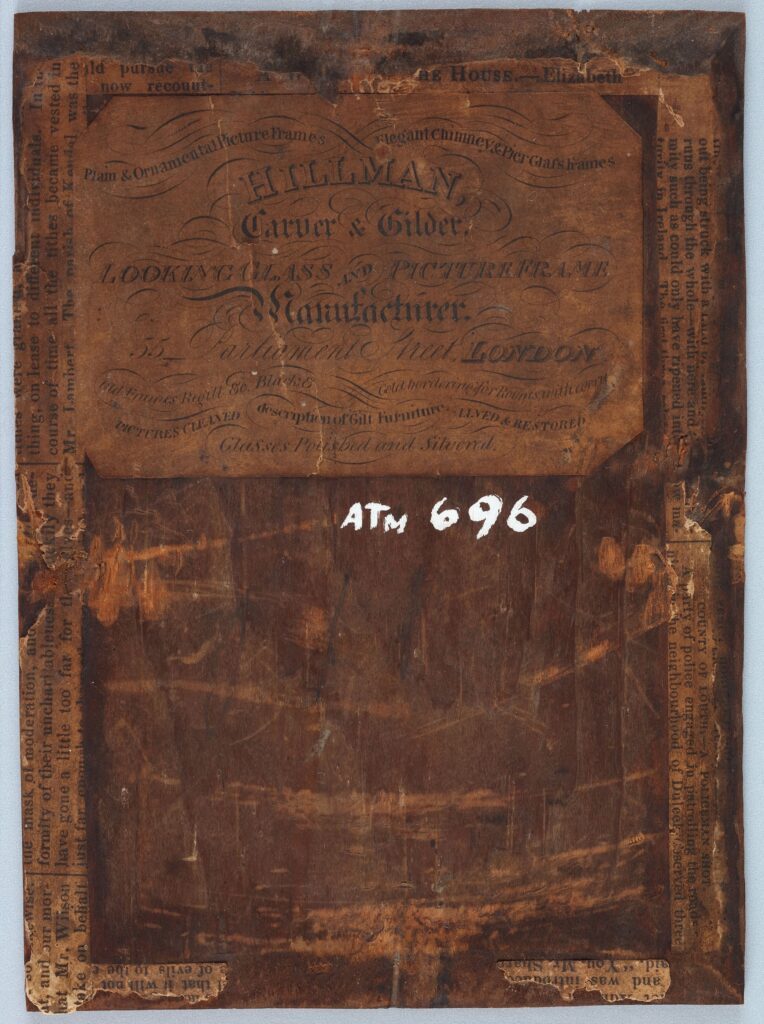

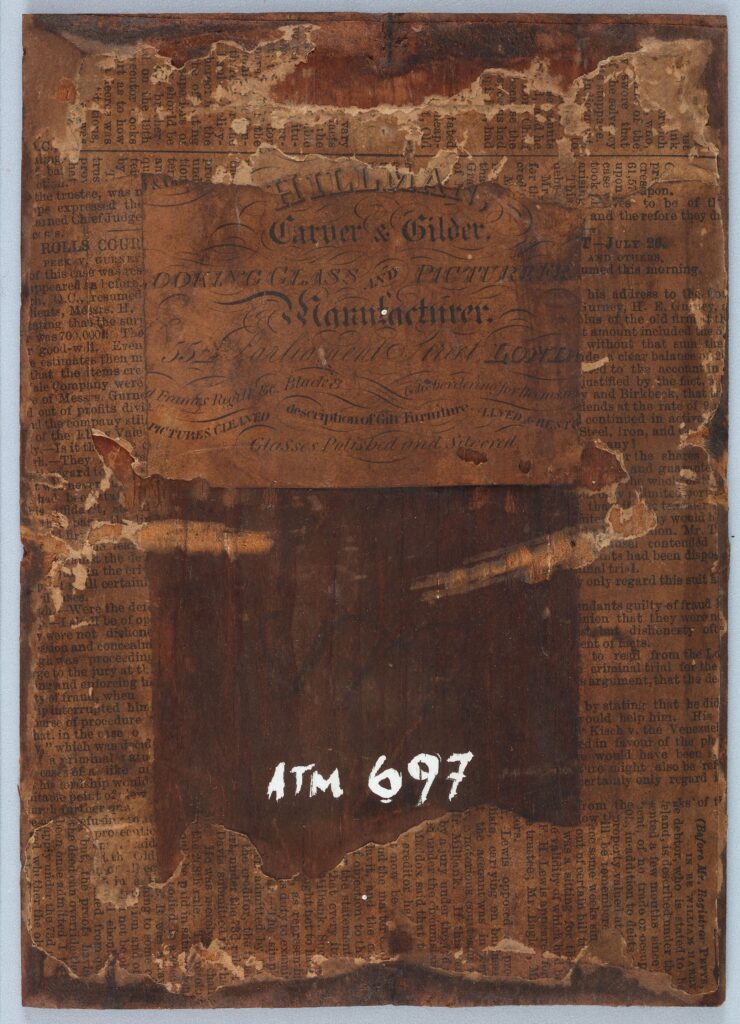

Na poleđinama dviju slika veduta (sl. 16. i sl. 18.) nalaze se tiskane naljepnice pravokutnoga oblika s odsječenim uglovima.

nepoznat autor / unknown author

Veduta

Engleska, XIX. st. / England, 19th c.

akvarel na papiru / watercolour on paper

16 cm x 11 cm

ATM 696

sl. 16

nepoznat autor / unknown author

Veduta

Engleska, XIX. st. / England, 19th c.

akvarel na papiru / watercolour on paper

16 cm x 11 cm

ATM 697

sl. 18

Naljepnica na ATM 696 (sl. 17.) u potpunosti je sačuvana, a onoj na ATM 697 (sl. 19.) poderan je znatan dio gornjega i bočnih dijelova, no tekst je ostao čitljiv, iako nepotpun. Sa sačuvane naljepnice tekst možemo iščitati u potpunosti, kako slijedi: PLAIN & ORNAMENTAL PICTURE FRAMES ELEGANT CHIMNEY & PIER GLAſS FRAMES / HILLMAN, / CARVER & GILDER, / LOOKING GLASS AND PICTUREFRAME / MANUFACTURER, / 55 PARLIAMENT STREET, LONDON / OLD FRAMES REGILT &C. BLACK & GOLD BORDERING FOR ROOMS WITH EVERY / PICTURES CLEANED DESCRIPTION OF GILT FURNITURE LINED & RESTORED / GLASSES POLISHED AND SILVERED.

Poleđina sl. 16 / The reverse of fig. 16

sl. 17

Poleđina sl. 18 / The reverse of fig. 18

sl. 19

Na adresi Parliament Street 55 u Londonu zabilježen je rezbar, pozlatar i trgovac slikama Edwin Hillman, koji je djelovao između 1835. i 1837. godine [5] kada upada u financijske probleme i proglašava bankrot. [6] Kako Hillman nakon proglašenja bankrota prestaje s radom, možemo utvrditi da su okviri slika nastali najkasnije 1837. godine, a posredno odrediti i terminus ante quem, odnosno da su slike vjerojatno naslikane prije te godine.

Osim oznaka i natpisa, u rijetkim slučajevima poleđina slike može sadržavati i sasvim novo umjetničko djelo. Umjetnički materijali kroz povijest često su bili skupi, ili iz drugih razloga nedostupni, pa su umjetnici štedjeli ponovno koristeći isti nositelj za novu sliku. Slika Kupačica Pierrea-Augustea Renoira iz stalnoga postava Muzeja Mimara, na svojoj pozadini otkriva novu sliku Djevojka u molitvi, znatno različitoga kolorita i ugođaja.

Behind the Painting – A New Look at the Objects from the Mimara Museum Collections

The front side of the painting is the one we experience first and the one we most often rely on to obtain information about a particular piece of art. The analyses conducted by art historians – formal, comparative, iconographic – are based on the observation of a work of art, where an encounter with an authentic piece, instead of a reproduction, is a key prerequisite for successful research. Together with archival research and familiarization with the currently available professional literature on the topic under research, these analyses enable the proposal on attribution and dating as well as evaluation of the piece in the context of the author’s work or artistic production, as well as the later role this piece plays in heritage.

Collected in museums as museum objects, works of art testify to the circumstances (time, space, culture, customs, technical achievements) in which they were created, that is, in the new, museum reality, they serve as documents of the reality from which they were extracted. However, this reality is not limited to the moment of their creation, so works of art, in addition to their authors and commisioners, testify to their later owners, changes in taste over time, ways and patterns of collecting and trading works of art – they testify to historical, social and economic context of the time in which they exist. It is precisely in this passage of time and changes in circumstances that the field of provenance research lies, and traces of these changes are often recorded on the objects themselves.

PROVENANCE

The term provenance (from the French verb provenir “to originate”) used by art historians and museum experts stands for the history of changes in the ownership and location of a work of art from the moment of its creation to the present time. Ideally, research into provenance can help attribute a specific work of art, but in most cases it will not be directly related to the attribution. Complete provenance implies an accurate list of the owners of the artwork, i.e., its places of storage, from the present time to the moment and place of its origin. Provenance research is a demanding operation that largely depends on the amount and availability of relevant sources, so complete provenances are rare, and gaps in provenance are common, especially for older works.

Sources for provenance research are very diverse and include auction catalogs, catalogs of collections and exhibitions, scientific studies and monographs, archival sources such as newspaper articles, sellers’ archives, sellers’ and buyers’ correspondence, various inventories, and museum documentation. The primary source of information on the provenance of a work of art is often found on the back of the artwork itself in the form of various markings. In this context, the front of the artwork and its back are equally valuable sources of knowledge, so art historians and museum experts often pay attention to this usually hidden side of the works of art.

MARKINGS ON THE BACK OF THE ARTWORK

The markings on the back of the painting can be very diverse and provide a range of information on the author of the art piece, its storage locations, owners and transfer of ownership of the art piece, such as auctions, donations and the like, as well as exhibitions where the artwork was shown. Also, the material of the surface with the painted layer, the way it was treated and its condition, visible only from the back of the painting, can provide valuable information about the origin of the piece, subsequent interventions into it or conditions in which it was stored.

Although author’s signatures are usually found on the front of the painting, sometimes they can be found on the back. An authentic signature will provide (or confirm) the attribution of the art piece, and if the author’s signature has changed over time, it may allow for a more accurate dating of the artwork. With their signature, authors sometimes name, date, mark the place of origin or write a dedication that gives us more information about who the artwork was created for or what purpose it served.

Owners of paintings may also leave traces of their ownership in the form of inscriptions or markings, which include signatures, initials, monograms, seals and coats of arms. Family coats of arms are often imprinted with wax stamps on the back sides of paintings. On the back of the painting Landscape with a Traveler by an unknown author (fig. 5), a completely preserved, square-shaped coat of arms is imprinted in red wax (fig. 6). The shield of the coat of arms is pointed at the bottom, while at the top it is finished with three spikes. Along the top of the coat of arms there are three six-pointed stars below which there is a hand with an open palm with an eye and a figure propped on one leg. The shield is held on each side by two unicorns, while on the back it is held by a crowned double-headed eagle. The affiliation of the coat of arms has not yet been determined with certainty, but it shows similarities (hand motif with eye, three stars, unicorns) with the coat of arms of the Phanariot family Manos. [1]

Changes in the location can also be traced if paintings bear customs stamps or markings of other government bodies. Customs stamps indicate that the painting was at a certain time on the territory of the country whose customs service left the stamp. On the back of the portrait of Eleanor of Portugal (fig. 7) there are two such stamps. In the upper right part of the back of the painting is a round ink stamp (fig. 8). Although the inscription in the seal is smudged, DOUANE CENTRALE can be read along the edge of the stamp, and in the central difficult-to-read inscription, it is only in the lower word that PAR[…] can be discerned. From the presence of this stamp we can conclude that at some point the painting must have passed customs control, and we assume this to have been on the territory of France. In the same painting to the left of the center axis towards the bottom there is another round ink stamp (fig. 9). Its edge is formed by two lines, and in the middle, one line surrounds the central coat of arms. Between the lines there is the inscription BUNDESDENKMALAMT and a shorter illegible inscription separated by asterisks. The Bundesdenkmalamt is the Austrian government body responsible for the preservation, protection, restoration and research of cultural heritage. It was founded in 1850 by the decision of Emperor Francis Joseph I as K.k. Central-Commission zur Erforschung und Erhaltung der Baudenkmale. [2] The seal of the Bundesdenkmalamt on the back of the art piece indicates that the object was once allowed to be exported from Austria.

If a painting is ever on sale at an auction house or a gallery, it is assigned an inventory number. For this purpose, auction houses typically used chalk – in the case of Sotheby’s it was yellow chalk – or ink. In the early 19th century Christie’s used black ink, but its labels changed over time, and today the paintings are usually marked with barcode stickers. By comparing the inventory number with the data in the archives of the auction house or gallery, it is possible to determine where and when the artwork was sold, and sometimes who sold it and at what price. Such information is extremely important in determining the provenance of the artwork, but also the changes in its past attributions. Past changes in the attribution and/or name of the art piece make it difficult to establish with certainty that the identity of the piece that is being researched is the same one which is mentioned in the correspondence and inventory lists of collectors or in the literature.

For paintings, as well as for other objects, inventory numbers are assigned when these objects become part of the museum collection, and sometimes special markings are assigned to objects lent for display outside the museum. All items in the holdings of the Mimara Museum were assigned inventory numbers containing the lettering part indicating the museum code determined in the professional register of the Museum Documentation Center in Zagreb and the numerical part indicating the order of entry of items in the museum holdings inventory. As a rule, inventory marks are applied to items directly, except in cases when the item could be damaged through the application of the mark. In such cases, the markings are made on another medium and attached to the item.

The back of the painting provides additional information not only with inscriptions and labels, but also with the material used in the making of the painting. The choice of material can indicate the time as well as the region in which the painting was created. In 15th century wooden panels were replaced by canvas as painting surfaces, which allowed for larger formats. Materials are sometimes marked with the manufacturer’s markings, which can help to pinpoint the location and/or the time when the painting was created. The choice of material and the surface production manner, i.e., the way boards are joint in the case of a panel painting, or the type of joint of the stretcher in the case of the painting on canvas, differ depending on the place and time of creation. Changes to the material can also provide information on the conditions in which the painting was stored or exhibited. A cracked painted layer or cracks in the wood surface may indicate hot and dry conditions, and warped surfaces may indicate that the painting was stored in humid conditions.

On the back of the Portrait of a Woman (fig. 14) there is an oval stamp with the inscription: MULLER FILS / PANNEAUX INDESTRUCTIBLES / CARTONS d’ÉTUDES / PARIS (fig. 15). The company Muller Fils operated in Paris from 1842 to 1855 under the leadership of Edmond Frédéric Muller, and was engaged in the production and sale of painting supplies (paints, canvases, panels, varnishes). [3] During this period, it was also registered under the names Muller Fils & Compagnie and Muller Fils & Cie. Patents were issued to the company in 1840 and 1844 for the production of colorless varnish and indestructible panels, [4] and in the same year it exhibited at the French Industrial Exposition in Paris.

On the backs of the two vedute (fig. 16 and fig. 18) there are rectangular printed stickers with truncated corners. The label on the ATM 696 (fig. 17) has been completely preserved, while a considerable part of the the upper and side parts of the one on the ATM 697 (fig. 19) has been torn off, but the text has remained legible, albeit incomplete. It can be read in its entirety from the preserved label as follows: PLAIN & ORNAMENTAL PICTURE FRAMES ELEGANT CHIMNEY & PIER GLAſS FRAMES / HILLMAN, / CARVER & GILDER, / LOOKING GLASS AND PICTUREFRAME / MANUFACTURER, / 55 PARLIAMENT STREET, LONDON / OLD FRAMES REGILT &C. BLACK & GOLD BORDERING FOR ROOMS WITH EVERY / PICTURES CLEANED DESCRIPTION OF GILT FURNITURE LINED & RESTORED / GLASSES POLISHED AND SILVERED. Parliament Street 55, London was where Edwin Hillman was situated. He was a carver, gilder and art dealer active between 1835 and 1837 [5] when he ran into financial trouble and declared bankruptcy. [6] As Hillman ceased to operate after the declaration of bankruptcy, we can establish that the picture frames were created no later than 1837, and indirectly determine the terminus ante quem, i.e., that the paintings were probably painted before that year.

In addition to markings and inscriptions, in rare cases the back of the painting may contain a completely new work of art. Throughout history, art supplies have often been expensive or otherwise unavailable, so artists would save by reusing the same surface for a new painting. The back of the painting The Bather by Pierre-Auguste Renoir from the permanent exhibition of the Mimara Museum reveals a new painting of the Girl in Prayer, with a significantly different color and atmosphere.

[2] Više o povijesti institucije/More on the history of the institution

[3] Muller Fils // Le Guide Labreuche. (pristupljeno 16. studenoga 2020./consulted 16 November 2020)

[6] London Gazette, br./Nr. 19501, 2. lipnja 1837./2 June 1837, str./p. 1418.London Gazette, br./Nr. 19506, 16. lipnja 1837./16 June 1837, str./pp. 1541 – 1542.